While ice is ubiquitous in the cosmos, snow requires a complex set of conditions to appear. Many gaseous compounds like methane, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen are below their freezing point on other planets, but not any molecule can form a snowflake. The unique electrostatic interactions of water molecules and a delicate balance of atmospheric conditions come together to determine what a snowflake will look like. As it falls, each snowflake retains the memory of its path through the sky, each slight change in temperature, humidity, and pressure resulting in unique and elaborate forms.

Photographs of snowflakes by Ukichiro Nakaya

Snowflakes have fascinated scientists for centuries, but their exact formation mechanism has long eluded them. How does a molecule as simple as water generate such a variety of different, elaborate, unpredictable structures? Japanese scientist Ukichiro Nakaya, who began researching snowflake formation mechanisms in the 1930s, is credited as the first human to ever create an artificial snowflake. After countless attempts at replicating the natural diversity of snow crystals, he realized he could grow snowflakes by suspending them on the tip of a rabbit's hair. Detailed reports and photographs of these experiments are collected in his beautiful 1954 book, Snow Crystals. Natural and Artificial.

Nakaya also developed the first diagram showing how atmospheric conditions determine the growth of ice crystals, demonstrating how each snowflake encapsulates precious information about the atmospheric conditions in which it had formed. Snowflakes, Nakaya famously said, are like “letters from the sky”: they memorize their own history through variation in form and structure. Many of the crystals in his “Nakaya diagram” — still used today in snowflake science — challenge our expectations of what a typical snowflake looks like.

Illustration of snow crystal formations by Ukichiro Nakaya.

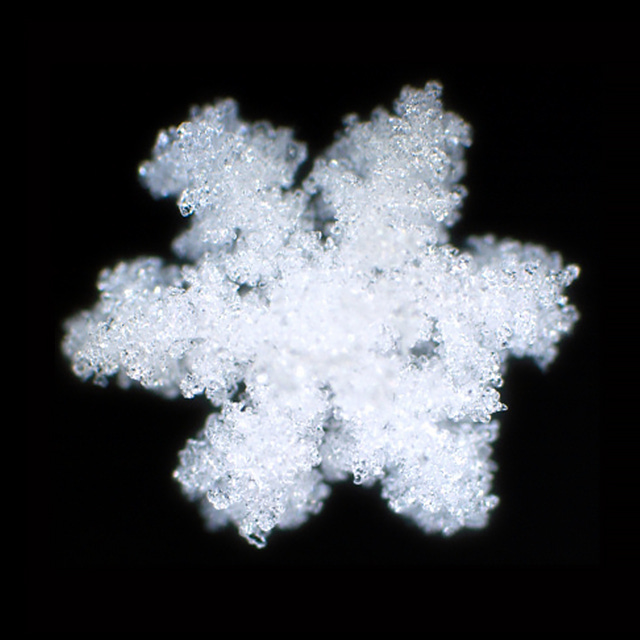

A while back, I came across a photograph of an unusual snowflake. Instead of its typical shape, it looked clumpy and disordered, only a rough approximation of the delicate and symmetrical snow crystals I had always seen before. The picture (captured by renowned snowflake scientist Kenneth Lbbrecht) was accompanied by an article explaining how the shapes of snowflakes are affected by climate change. As the crystals fall through an increasing number of pockets of hot air, the article explains, the surface layers of the snowflakes melt, disturbing the crystallization process and creating small and disordered pellets of ice known as rime.

Snowflake covered in rime photographed by Kenneth Libbrecht

There are currently no scientific papers (that I know of) supporting this finding. Yet, it sounds likely that as the climate changes, snowflakes, dependent as they are on the delicate balance of atmospheric conditions of the Earth, will irreversibly change, too. Regardless, at least for me, the image of this diseased snowflake captured the emotional complexity and fragility of living through catastrophic times more than satellite images of remote icecaps seen from space. This made me wonder about the possibility of representing global catastrophe as small and intimate, and whether this can help us open ourselves to different forms of empathy.

The photograph of the deformed anthropocenic snowflake also reminded me of the theory of the memory of water. The idea was popularized in the 1990s by another Japanese researcher, Masaru Emoto. According to Emoto, the shapes of ice crystals are determined not only by atmospheric conditions, but also by other, more subtle, influences: music, electromagnetic radiation, and even human thoughts and emotions. In his popular experiments, he reports images of ice crystals after exposing water to either positive or negative affirmations, insults or prayers, Mozart symphonies or heavy metal tracks. When water was touched by positive emotions, it crystallized in beautiful snowflakes. When it was exposed to negativity, it formed asymmetrical and chaotic crystals.

Water crystallization experiments by Masaru Emoto

There is no evidence, of course, that Masaru Emoto’s experiments ever worked: his theories are well-known examples of pseudo-science. Yet, I am more interested in understanding what these images tell us about our relationship with materials, and how the mysterious vitality of ice crystals has become a mediator to process our own emotional and social wounds. “The earth is searching”, wrote Emoto in his book The Hidden Messages in Water. “It wants to be beautiful. It wants to be the most beautiful that it can be. Earlier I said that we could define the human being as water. I am quite certain that the water in the people who look at the photographs of crystals undergoes some form of change”.

In recent years, several thinkers and artists have begun looking at water in a renewed light. Among them, Astrida Neimanis, in her influential book Bodies of Water, has reflected on the implications of rethinking the human body as watery, not contained by hard surfaces but fluid, trans-individual, and always in motion. In her book, water becomes a metaphor for a new kind of feminist embodiment (aptly named hydrofeminism) in which all bodies are connected and relational. The book strongly argues against the objectification of water as a universal resource, claiming that we should consider each body of water as unique and particular. Yet, much like in Masaru Emoto’s work, it seems to me that Neimanis’ book is moved by an urge to find within water a unifying principle, a universal element of purity in a diseased world.

Ukichiro Nakaya’s first artificial snowflake

In contrast to other snowflake collectors (the most famous being Wilson Bentley in the United States), Ukichiro Nakaya’s work conveys a fascination with asymmetry and difference. The same snowflakes that Masaru Emoto would have considered deformed and unhealthy were, to Nakaya, testimonies to the complexity and variety of matter. To him, broken, composite, and crooked crystals contained unique stories that the beautiful (and often retouched) photographs of perfectly symmetric crystals were unable to convey. Today, what “new materialist” theories often fail to do — the reason why they so often fall prey to a form of over-complicated new-age spiritualism — is to actively listen to what materials have to tell us. As we rethink our relationship with materials from the ground up, I feel that we should be careful not to project our too-human paradigms of beauty and order onto nonhuman matter, or to use matter as a passive canvas for our own moral and philosophical meanings.

References

Ukichiro Nakaya, Snow Crystals: Natural and Artificial, Cambridge University Press, Harvard, 1954.

Masaru Emoto, The Hidden Messages in Water, Beyond Words Publishing, Hillsboro, 2001.

Astrida Neimanis, Bodies of Water. Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, Bloomsbury, London and New York, 2017.

![[animate output image] [animate output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!VDuc!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd162b9e0-b001-4354-a929-24e4a9d2cbbb_676x695.gif)

Your beatiful text remind me this video, Jackie Wang "Oceanic Feeling and Communist Affect": https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=ma6y2IFDfUY

The Dreaming Jewels!