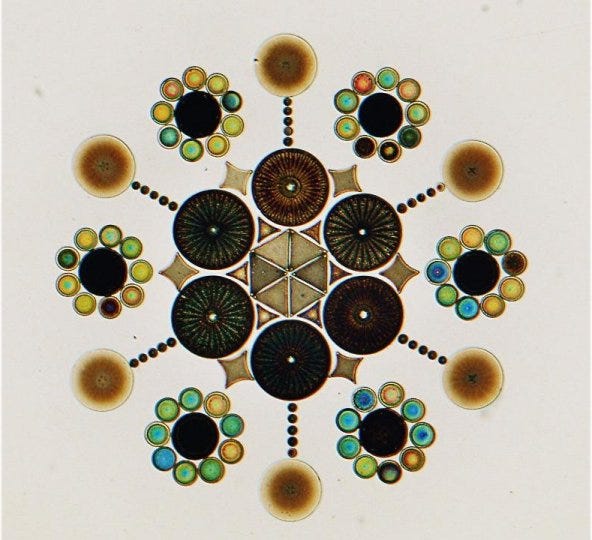

Although we usually think of the intersection of art and biology as something that has existed for a couple of decades at most, since the early days of modern science people have been creating art with its objects and its processes. The microscopic composition you see in the picture above was assembled in the 1880s; the tiny shells that compose it are the remains of microscopic organisms known as diatoms. Diatoms are photosynthetic algae enclosed within incredibly elaborate shells called "frustules," made of biogenic silica, which is essentially a type of biological glass. We cannot see them with our naked eyes, yet they are everywhere around us—anywhere there is water and light.

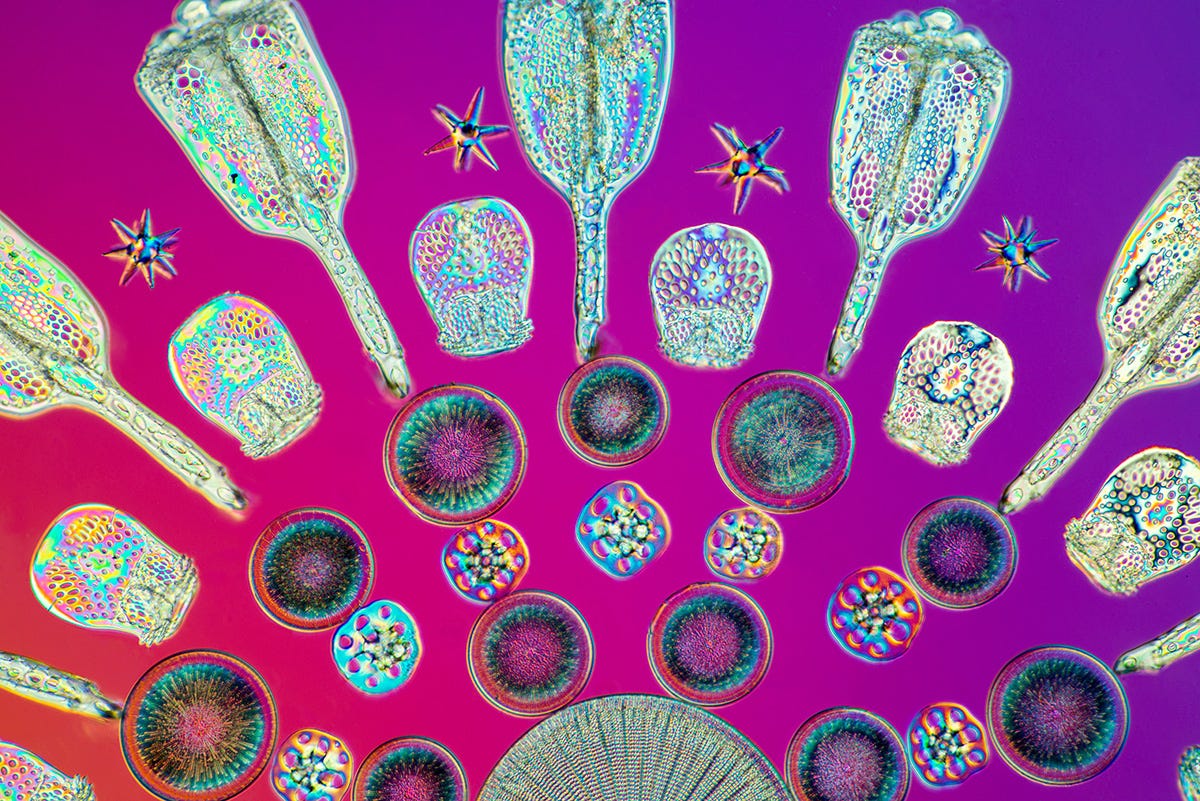

The complex, symmetrical, and diverse shapes of diatoms fascinated scientists since the early days of microscopy, when they were mounted on glass slides and commonly used to test the resolving power of microscope lenses. Back in those days, before we were able to artificially craft comparably accurate structures on the microscale, the shells of these microscopic organisms were the measure of our capacity to see.

Originating as an epistemic necessity, the practice of collecting diatoms and mounting them on microscope slides underwent a gradual transformation into an elaborate art form. Throughout the 1800s, the complicated craft of arranging diatoms into captivating microscopic compositions gained popularity, culminating in the work of German microscopist Johann Diedrich Möller, the author of all the arrangements you see in this post.

Möller was capable of arranging thousands of tiny frustules, only fractions of a millimeter in size, into a single display with painstaking precision, moving them around with a single thin bristle. His masterpiece is the Universum Diatomacearum Möllerianum: a single slide containing 4026 different diatom species, which reportedly took over four years to complete. In 2015, photographer and microscopist Jef Schoors captured and digitalized the entire Universum slide, granting us the opportunity to directly explore it. You can browse it here.

Today, we are accustomed to contemporary artists working with methods and materials borrowed from the biological sciences. Often, these artworks do not merely ask us to marvel at the "beauty of nature"; rather, they prompt us to reconsider the processes of knowledge that make that very "nature" accessible to our human eyes. In doing so, they also shed light on the implications of our gaze on our relationship with the non-human. It is this epistemic and political, in the broadest sense, aspect of the convergence of art and science that I find especially significant.

We can look at diatoms as living art forms, yet they are also crucial to human existence. Nineteenth-century microscopists were unaware of this, but the estimated two million different species of diatoms alive today produce a large portion of the oxygen you and I breathe - between 20 and 50 percent according to most estimates. While invisible to the human eye, diatoms are visible from space. Astronauts have reported observing vast "diatom blooms" spanning hundreds of kilometers across the ocean's surface.

In a way, diatoms provide precious insight into how scale influences our knowledge of things, showing us how everything (including ourselves) exists across a range of scales, from the microscopic to the geophysical. The concept of "ecology" held a vastly different meaning, if it had any meaning at all, for people in the 1800s. Regardless, it is unsurprising to me that Ernst Haeckel, who originated the term in its modern connotation, dedicated a significant portion of his life to drawing and contemplating diatoms.

Understanding how art can help us access the intricate complexities of ecological reality would require an entire book, and fortunately, Timothy Morton already wrote that for us. It is possible that the pure objectivity of science alone is inadequate in the face of ecological beings, and maybe that’s why art and science have never truly been two separate endeavors.

References

J. D. Möller’s Prepared Slides Rediscovered. Mikrobiologische Vereinigung Hamburg [Internet].

Timothy Morton. Being Ecological. The MIT Press, Cambridge, 2019.

Tutto stupendo